Beauty as Duty: The original influencers?

In the absence of the many men conscripted into military services during the Second World War, women stepped in to help keep Britain running by temporarily adopting ‘masculine’ roles at home and in the workplace.

However, one decidedly ‘feminine’ approach that British women were encouraged to contribute to the war effort was through their appearance.

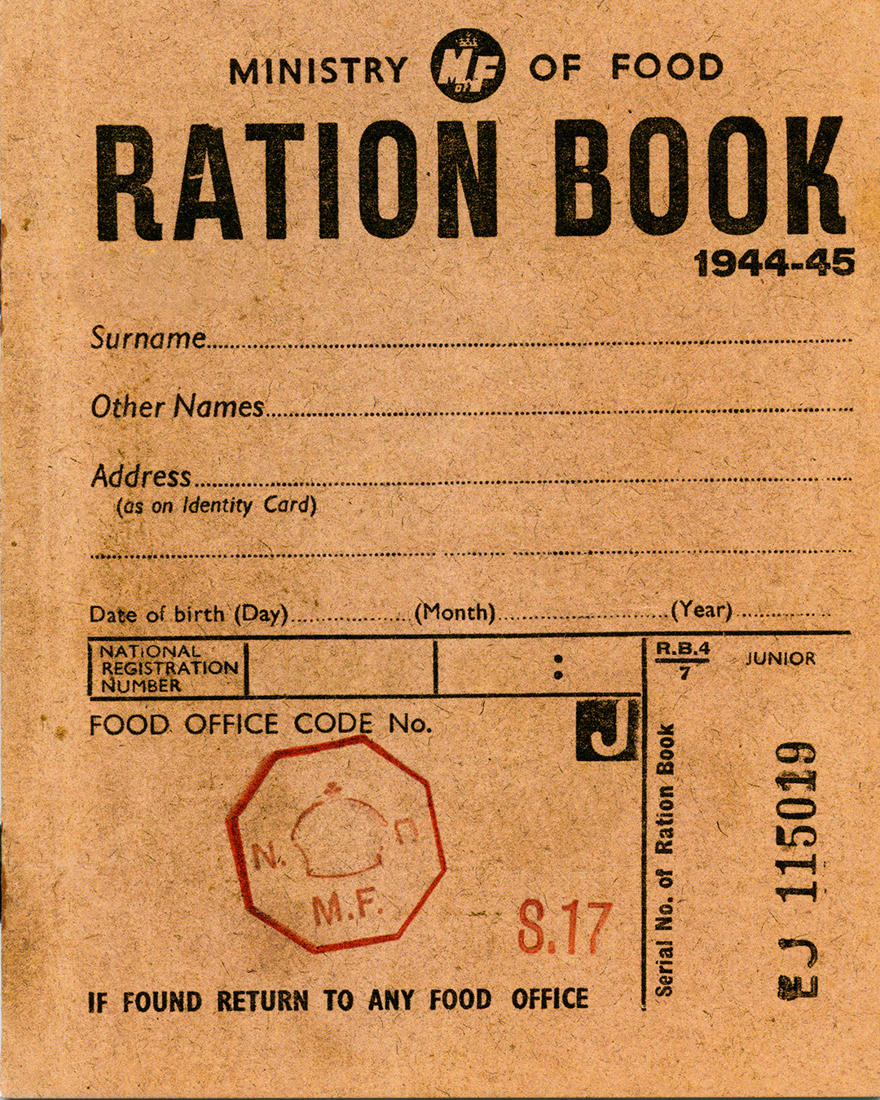

The rationing of clothes and other personal items during the Second World War is well known and has been extensively written about (see, for example, Juliet Gardiner); however, the ‘Beauty as Duty’ aspect of this is arguably less well documented. The scheme acted a visual marker of gender identity at a time when traditional gender roles were blurring to fulfil wartime needs and ensure victory. Here we would like to shed some light on this and also suggest some relevance to today’s society.

So, what was ‘Beauty as Duty’? As Pat Kirkham has so eloquently written, it was part of a ‘national call for a united front of individual female front to keep up appearances and maintain an illusion of normality in the face of extraordinary odds’. In practice this meant, whatever the odds and difficulties as a woman, it was considered a national and patriotic duty to look after your appearance and make sure your hair, make-up and clothing were as good as possible, using whatever means were available to you, a visual embodiment of fortitude and a stiff upper lip, attempting to positively influence Britain’s collective morale.

Whilst products such as Pond’s face cream were popular, it could mean using alternatives to traditional make-up and hair products, which, although not officially rationed, were in desperately short supply as factories were given over to war production. This might mean buying from the ‘grey’ and black market or re-purposing products such as boot polish to be used as mascara, using sugar water instead of wave setting lotion on hair and extending the life of a precious lipstick by melting it in an egg cup or adding almond oil to it (Virginia Nicholson). Resorting to the ‘grey’ or black market, apart from being thought unpatriotic, was not without danger as some of the ‘back street’ preparations being sold might contain dangerous substances such as arsenic. Some face powders on examination were nothing more than coloured, powdered chalk and cheap scent (Chamberlin). ‘Beauty as Duty’ could come with a significant price, and not just in cost. As the Daily Express observed in 1941, these ‘back parlour beauty aids’ were being sold at the rate of one million pounds worth a year because as a manufacturer noted, ‘the public is buying more cosmetics today than ever’.

The Beauty as Duty ethos and putting on a brave front was also considered such an important tool in the government’s propaganda work that there were special dispensations for some workers, for example munitions workers, considered vital in the war effort, were granted special allowances of high-grade face make-up, with cosmetics brand MaxFactor additionally distributing products to women in these settings. A special shade of lipstick, ‘Burnt Sugar’ was created especially for women in the services by the brand Elizabeth Arden. It was supposed to match well with khaki. The government saw the issue of keeping up morale in this way as so important it saw fit to issue a booklet in 1942 encouraging people to ‘Look to your Looks’.

Propaganda is such that when the government gets involved, it must be for an important reason or if there is a problem with the issue, but how much notice people ever took is open to debate. Arguably, far more significant in terms of public awareness were the adverts and general tone of women's magazines. Magazines were a crucial tool in communicating beauty propaganda to women in Britain. Wartime editor of Vogue, Audrey Withers, was ‘convinced that Vogue…could be a powerful weapon of the war in its own right’. Through a collective effort, Vogue sought to instil that beauty, ‘in measured amounts – was not frivolous, it was a patriotic duty’. It exemplified this in 1941 by printing:

‘It is axiomatic that the good spirits of the fighting men depend on the civilian and more particularly the female of the species. And what do hers depend on? Well largely on her clothes…this business of looking beautiful is largely a duty’.

Vogue, 1941

Despite shortages of paper, women’s magazines enjoyed a boom time, with copies being passed around friends many times over.

Many of the adverts in them reflected this ‘Beauty as Duty’ discourse. For example, a soap advert from 1940, purported ‘Looking our best is one of the ways in which we can help to keep up national morale’. This is echoed by popular underwear brand Berlei, who started one of their adverts with ‘it’s bad for morale to let figures go’. Propaganda and the ‘Beauty as Duty’ discourse further seeped into clothing, as the ‘Make-do and Mend’ scheme encouraged households to prolong the lifespan of their clothing and textiles through traditional needlecraft and dressmaking techniques. Against a background of clothes rationing and coupons, which basically equalled one complete outfit per year, people got creative to refresh their tired wardrobes. Hats were ‘off ration’ but also in short supply, so decorating them with ribbons and lace became popular way of demonstrating individualism.

Wartime industrial work carried out by women necessitated appropriate clothing. Headscarves were worn by many to protect long hair from machinery and the dirty, dusty conditions of their new employment. This was recognised by fashion brands as an opportunity for disseminating propaganda. The scarves made from silk; and later rayon when resources became scarcer, were adorned with “visible markers of national unity and support for military and political goals”.

The most notable examples were produced by Jacqmar often with ‘co-operation’ from the Ministry of Information. At this time, Jacqmar was a luxury brand with aspirational marketing. One piece from American Vogue in 1942, showcases their scarves on ‘war workers’. However, these war workers were in fact wealthy members of British high society. The scarves: once primarily bought by the wealthy, were now attainable by more women with financial independence afforded by war work. A shop assistant from a Chester retailer describes “the factory girls have all the money now and come in”. The scarves acted as a visual cue of patriotic femininity, as well as a display of financial independence.

Brooches, often depicting the regimental badge of a loved one, were also a popular way of not only being patriotic but also accessorising an outfit and keeping that person at the forefront of your mind. For the better off, Ciro offered a version for the royal tank regiment with diamonds and enamel for four guineas- cheaper versions were available! By the end of the conflict, The Royal School of Needlework (RSN) had also developed and released kits for the public to stitch their own regimental badges. In a press release circulated to all allied countries, Lady Olive Dorrien Smith, RSN Principal, championed the therapeutic properties of embroidery over other needlecrafts due to the level of focus required. Demonstrating potential psychological benefits in addition to the aesthetic.

Despite the notion of everyone being ‘in it together’ there was significant grumbling owing to the contrasting wartime experiences, as arguably, the better off a person was, the easier time was had regarding rationing (see Angus Calder’s seminal work).

Despite this, ‘Beauty as Duty’ could all be seen to contribute to some sense of positive citizenship in significant contrast to today’s sometimes fractious society. Pruyers, Blais and Chen remind us of Dalton and Denters et al.’s ideas that positive (or good) citizenship or civic spirit can be interpreted as ‘good citizens [who] vote in elections, pay their taxes, obey the law, and are well informed and active in social and political life’.

This could also include acting in the wider interest of that society. We have arguably seen that ideal crumble over the recent decade or so, with tensions around areas such as national identity and migration, however on the Home Front during the war, the government actively promoted the idea of a cohesive society, and everyone doing their best to maintain their appearance and morale, which could be seen as an example of this effort.

Aside from potentially boosting the nation’s collective morale, diarist Nella Last wrote in 1939, that when she looked ‘washed out’ before her son was deployed, she wore her ‘gayest frock and made up rather heavily’ with modern research supporting the efficacy of this. The theory of enclothed cognition encapsulates the powerful associations individuals have with clothing and the potential impacts on how individuals feel and act.

As explored by Hajo Adam and Adam Galinsky ‘when a piece of clothing is worn, it exerts an influence on the wearer’s psychological processes by activating associated abstract concepts through its symbolic meaning’. Shakaila Forbes-Bell, illustrates this by proposing ‘if you associate a yellow jumper with happiness, then you will embody that feeling of happiness when you wear it’. As Kirkham notes, one woman recalled that her lipstick and engagement ring were two vital protections against Hitler. She would ‘never go out without those’. Beauty as Duty was not just about national morale but personal morale too.

We are all now familiar with the idea of the ‘Influencer’ in society. As Arriagada and Bishop suggest ‘Influencers are highly visible tastemakers who professionally publish content on social media platforms’ and (most importantly) influence people to buy the goods they are promoting. Arguably, the whole idea of ‘Beauty as Duty’ and the adverts that encouraged this could be seen as an early version of the concept of an Influencer. Many of the ideas might seem superficial, especially set against the German ideal of sacrifice and hardship to support the war, however in playing a part in keeping morale high, often with a patriotic undertone, and providing women in particular with a distraction from their war work it was an important aspect of the war on the Home Front. Whilst ‘Beauty as Duty’ may not be directly applicable in a modern society due to its themes of misogyny and objectification, there is evidence that individuals of all genders could influence their own wellbeing through the theory of enclothed cognition and throwing on their ‘favourite yellow jumper’.

Dr. Elspeth King is a lecturer in history at the University. One of her particular interests is the Home Front in Britain during the Second World War.

Esther Dobson is an RKE Facilitator in the Doctoral School, and has just completed a master’s degree in history looking into the value of needlecraft and clothing provision to women in Britain during the Second World War.