How does physical activity affect the health of those with bipolar disorder?

Gemma McCullough, a PhD student at the University of Worcester with our Bipolar Disorder Research Network (BDRN) is conducting research to find out if and how physical activity can benefit those with bipolar disorder.

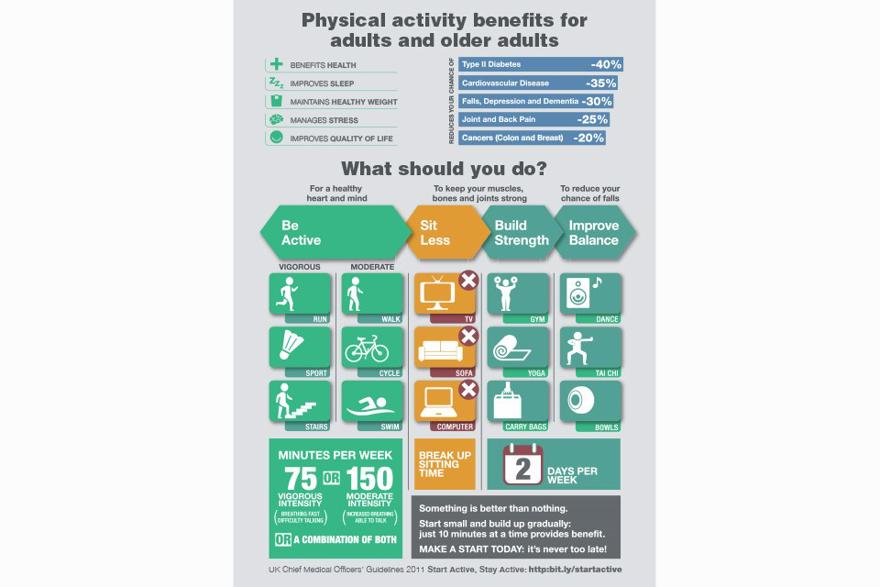

Being physically active has many well-known physical health benefits, such as staying fit and healthy, improving core strength, and managing and maintaining a healthy weight. Being physically active on a regular basis also reduces your risk of developing certain medical conditions such as type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and certain cancers.

In recent years, researchers have investigated the links between physical activity and mental wellbeing. Being physically active through the form of specific exercise, or making certain lifestyle changes can provide:

- Social companionship

- A sense of achievement

- Opportunities to enjoy the green outdoors

- The chance to take some time out to de-stress.

Due to the collective benefits of regular physical activity, it is also now thought to act as a protective factor against common mental health difficulties such as depression and anxiety.

Despite knowing that physical activity is good for our physical health and mental wellbeing, many of us do not find it easy to meet the recommended amount of physical activity for the week. The Chief Medical Officer’s report (see summary in image) recommends that adults over the age of 18 should engage with at least 75 to 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity each week, and engage in activities aimed at improving balance and improving strength at least twice a week.

However, little is known about how physical activity levels may affect people who have a mood disorder called bipolar disorder, where individuals experience both severely high and low moods.

Understanding bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is characterised by periods of elevated mood (referred to as mania) and usually, contrasting episodes of depression.

Although people often perceive bipolar disorder as simply being ‘happy one minute and sad the next,’ or as ‘someone who has lots of mood swings,’ most people with bipolar disorder experience discrete periods of symptoms pertaining to a particular mood state (called an episode), with periods of wellness in between. However, some people do experience frequent episodes or ‘rapid-cycling’ and others can experience what is known as ‘mood lability’ where their mood can change rapidly day-to-day or even within the same day. Bipolar disorder is therefore a complex and ever-changing mood disorder, which affects around 1% of the population worldwide.

We do not know exactly what causes bipolar disorder, but it has been shown to be a multi-factorial condition, meaning that several things contribute to how the illness is expressed in an individual, such as family history, and a range of social, psychological and environmental factors that can also be triggers for mood episodes.

A group photo of our Mood Disorders Research Group team here at the University.

A group photo of our Mood Disorders Research Group team here at the University.

The Bipolar Disorder Research Network (BDRN) at the University of Worcester is primarily interested in understanding more about the causes of bipolar disorder. This is where physical activity may play an important role in regards to mood regulation in people living with bipolar disorder, as we know that regular physical activity is good for our mental health and wellbeing, and protecting against depression

So where does my research fit in?

Over the last three years, I have been carrying out a PhD research project in collaboration with the BDRN to try to understand what the relationships are, if any, between physical activity, inactivity, and mood in people with bipolar disorder.

The aim of my research is to try to answer questions such as: ‘what changes first, mood or physical activity levels?’ Answering this question could be beneficial in understanding how lower physical activity levels may impact depression, and whether higher physical activity levels impact on mania.

How do we investigate this?

To explore these questions, I carried out a series of initial interviews with people living with bipolar disorder to explore what they perceived to be the relationship between their activity levels and mood.

Many participants talked about routines, the impact of medication, and how physical activity was a useful way of managing mood: for trying to be more active when they felt depressed, and less active when they felt manic. The interviews also revealed that the real challenge in regards to physical activity, inactivity and mood, was maintaining a balance. This is particularly interesting, as we typically think of physical activity as a completely positive thing, and inactivity as a negative thing, however these interviews provided evidence of physical activity being unhelpful for mania, but helpful for depression, and inactivity being helpful for mania, but unhelpful for depression.

In order to explore physical activity, inactivity and mood in more detail, wearable activity monitors and mood diaries were then provided to over fifty BDRN participants, allowing them to monitor and track their activity levels and mood over a 7-day period.

Participants felt this was important research and provided very detailed accounts of their day-to-day mood changes and activity levels. I am currently in the process of combining this data with the interview responses, as well as a series of questionnaire responses to gain a more holistic picture of what the relationships are between physical activity, inactivity and mood symptoms, in people with bipolar disorder.

The results from my research could be used to inform physical activity interventions targeted at people living with bipolar disorder, as well as aiding people with bipolar disorder to help balance challenging mood symptoms. My research will also give an insight into the role physical activity and inactivity plays in the causes of bipolar disorder and the expression of particular symptoms.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my research supervisors: Professor Derek Peters (Director of Studies), Professor Lisa Jones and Professor Eleanor Bradley, as well as the participants and members of the Bipolar Disorder Research Network.

Gemma is a full time PhD student at the University of Worcester. She is a member of Worcester’s Research Students Society and a graduate member of the British Psychological Society.

All views expressed in this blog are the Academic’s own and do not represent the views, policies or opinions of the University of Worcester or any of its partners.